Research

Background

Most organisms possess an internal timer or circadian clock that allows them to regulate their physiology to better adapt to our continually changing world. These circadian clocks generate roughly 24 hour rhythms in physiology and behavior that are maintained even in the absence of environmental cues. Although the molecular components of circadian clocks are not conserved across higher taxa, in all organisms studied these clocks are cell autonomous oscillators and in eukaryotes are composed of complex transcriptional networks.

The Harmer lab uses forward and reverse genetics, genomics, biochemistry, and physiological studies to better understand the nature of the plant clock and how it helps shape plant adaptations to ever-changing environments. We use techniques ranging from ‘omics approaches to field-based studies to better understand how the plant clock works and how it promotes fitness in the natural environment.

Molecular nature of the circadian oscillator

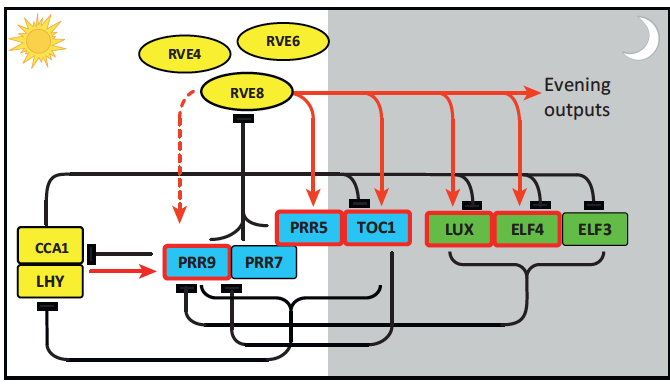

Model of the plant circadian clock, from Hsu and Harmer (2013) Trends Plant Sci

Our model system for studies into the molecular nature of the plant clock is Arabidopsis thaliana. Using this powerful genetic model, we and others have identified a large number of plant-specific transcription factors that regulate each other’s expression via multiple feedback loops to form a complex transcriptional network.

Why is the plant clock so complex? The animal circadian network has far fewer components and provides reliable timekeeping. We have used genetics and computer modeling approaches to investigate this question, formulating a simplified model of the clock and testing the requirement for different classes of components in different environmental conditions.

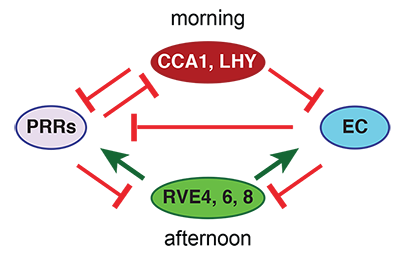

Simplified model of the plant circadian clock, from Shalit-Kaneh et al (2018) PNAS

Our results (Shalit-Kaneh et al (2018) PNAS) suggest that this high degree of network complexity provides rhythmic robustness across the wide range of environmental conditions that plants are subject to on a daily and seasonal basis. We are currently investigating the role of individual clock factors under specific environmental conditions.

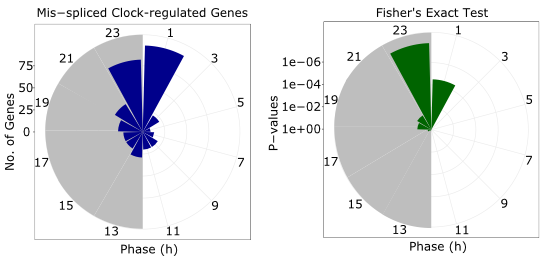

We are also investigating how XCT, a protein conserved across eukaryotes (Martin-Tryon and Harmer (2008) Plant Cell), links the plant circadian oscillator with other fundamental cellular processes. The Arabidopsis XCT gene rescues growth phenotypes in fission yeast mutant for the S. pombe ortholog (Anver et al. (2014) EMBO reports), suggesting deeply conserved functions for this protein. Indeed, we have recently found that XCT associates with other highly-conserved proteins to regulate pre-mRNA splicing (Zhang et al. (2023) Plant Physiology) and DNA damage responses (Kumimoto et al. (2021) Frontiers in Plant Sciences). However, our data suggests that XCT may have splicing-independent roles in the circadian system.

Dawn-phased genes are more likely to be aberrantly spliced in xct mutants, from Zhang et al (2023) Plant Physiology

We are further investigating the biochemical functions of XCT and determining the cellular pathways in which it acts.

Circadian and environmental control of growth and development

Sunflower heliotropism

In previous work, we found that the circadian clock ‘gates’ the sensitivity of Arabidopsis seedlings to auxin (Covington et al. (2007) PLoS Bio); that is, the degree of response to auxin differs according to the time of day. We then wondered in what circumstances it would be advantageous for plants to have the complex temporal regulatory network of the circadian clock linked to the auxin signaling network, a key regulator of spatial control of plant growth.

This led us to investigate a possible role for the plant clock in sunflower heliotropism, or solar tracking. Although many plants are robust solar trackers (Ehleringer and Forseth (1988)), heliotropism is particularly obvious in domesticated sunflower due to its long single stem. Remarkably, the leaves and stems of sunflower plants not only bend from east to west during the day, following the apparent movement of the sun, but also bend from west to east during the night in anticipation of sunrise. We demonstrated that the circadian clock plays an important role in solar tracking, especially in nightime reorientation.

Animation of solar tracking sunflowers, summary of results in Atamian et al (2016) Science.

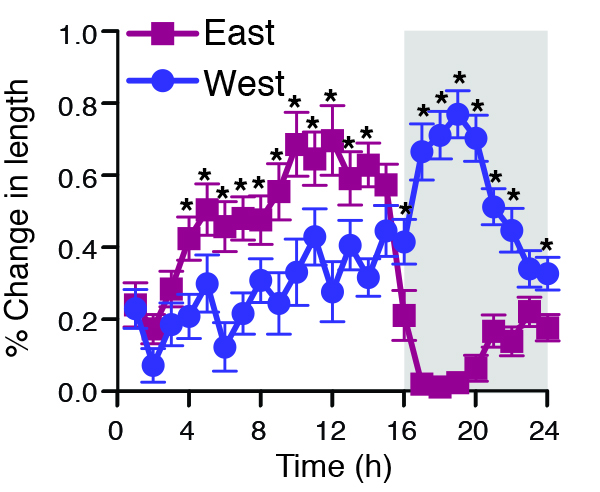

We found that the back-and-forth bending of young plants is driven by asymmetric growth on the east and west sides of the stem, with the east side growing faster during the day and the west side growing faster at night.

We are particularly interested in understanding the molecular growth pathways controlling the different growth rates across this symmetric organ. Current results suggest that distinct growth pathways regulate daytime and nighttime bending movements, a possibility that we are eagerly investigating.

Asymmetrical growth across sunflower stems drives solar tracking movements Atamian et al (2016), Science.

Environmental and circadian control of flower development

During our analysis of solar tracking in sunflower, we became intrigued by a possible role for the circadian clock in regulation of flower development and pollination. Although sunflower heads appear to be single flowers, they are actually composed of hundreds or even thousands of individual florets grouped together into a flower-like structure called a capitulum. The individual disk florets found in the centers of these capitula in sunflower and many other members of the Compositae are protandrous; that is, they are male one day and then female the next day, a reproductive strategy that promotes outcrossing.

We found that the circadian clock helps produce the near-uniform eastward orientation seen in mature sunflower plants Atamian et al (2016) Science. Moreover, we demonstrated that this eastward orientation affects the timing of floral development, pollinator visits, and male reproductive success Creux et al (2021) New Phytologist.

The circadian clock also plays a more direct role in floral development. Late-stage floret development progresses in a stepwise manner from the outside of each disk in towards the middle. In domesticated sunflower, with its large capitulum, three or four rings of florets mature simultaneously on a given day. We have found that the circadian clock along with light and temperature signaling pathways regulates the pattern and precise timing of floret development and that this affects pollinator visits and reproductive fitness Marshall et al (2016) eLife.

Bee collecting pollen from male-stage florets (Creux et al, unpublished)

We are currently investigating the molecular pathways controlling the timing of late-stage floret development in primarily outcrossing sunflower and comparing them to those governing floret development in its self-pollinating relative, lettuce.